Nationwide controversy has once again sparked a debate about the efficiency and side effects of vaccines. Recently confirmed Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has sparked a discussion into vaccines that has left many in the country divided.

A Long History of Vaccine Success

In parts of Asia and Eurasia, inoculation was practiced long before it was fully understood. Both China and India had documented forms of inoculation as early as the 16th century. In China, the first written mention of inoculation can be found in a book from 1549, while references found in ancient Sanskrit texts suggest that inoculation in India may have been practiced for thousands of years. While much of this evidence is speculative, the practice spread to the Ottoman Empire around the 17th century, where it was considered an effective measure for preventing the smallpox virus.

The technique used many of the same ideas as modern vaccines, intentionally infecting a person with the virus in a controlled manner, leading to a milder illness and resulting immunity. While this method was not without risks, it was a safer alternative to contracting the disease naturally.

Despite the early adoption of inoculation in Asia, the practice was not as developed in parts of Europe. In Scotland and mainland Europe, a comparable method of inoculation, known as “buying the pocks” was practiced. This involved purchasing smallpox material, which would then be introduced to a child in various ways, however, these methods were inconsistent and seldom recorded. Therefore, the practice did not gain widespread acceptance until inoculation was more formally introduced in the mid-17th century.

In the early 18th century, the practice of inoculation made its way to North America by way of an enslaved man named Onesimus. He shared his knowledge of inoculation, originating in modern-day Libya, with his owner, Cotton Mather. At this time, the city of Boston was experiencing a smallpox epidemic–the worst ever recorded. Onesimus’s knowledge led to the first successful smallpox inoculations in the American colonies.

In the latter parts of the 1700s, Edward Jenner built upon the ideas of Onesimus and other earlier scientists who studied how to cure smallpox. Jenner collected the pus from a previous smallpox patient and then used it to purposely infect the child with smallpox. The child never showed any symptoms and never faced any effects from smallpox in the future.

Jenner is credited for making the first modern vaccine and is hailed as the “father of immunology” today. Later scientists then built upon Jenner’s research, leading to a greater understanding of vaccines. The United States later made vaccines for smallpox compulsory for young children in the early 1900s.

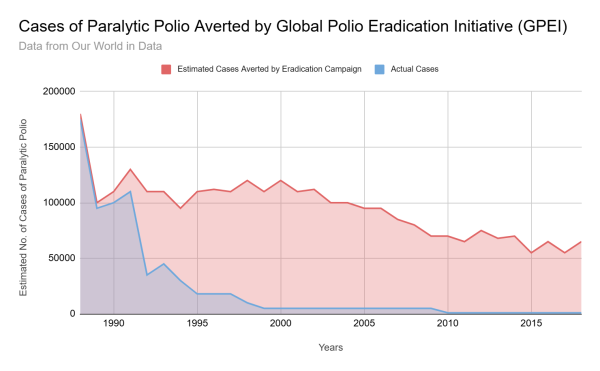

In the mid-1900s, polio saw a spike in the United States. In 1952, polio killed over 3,000 in the United States alone. Scientist Jonas Salk publicly released the polio vaccine in 1955. Thanks to the vaccine, cases of polio in the Americas and Europe were eradicated in 1994. Polio still exists in several African nations today, however, the World Health Organization has taken numerous initiatives in less developed countries to supply and administer the polio vaccine. Today, 93% of one-year-olds in the United States are vaccinated against polio.

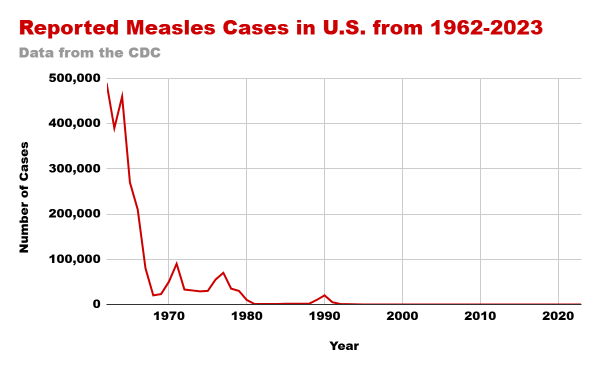

Like polio, measles saw many deaths both domestically and abroad. Prior to the measles vaccine in the United States, it was estimated that roughly 500 people died of measles each year, with an additional 45,000 being hospitalized. Scientists were able to develop a vaccine that not only could stop the spread of measles, but also stop the spread of the Mumps and Rubella diseases, and was released in 1971. As a result, measles was largely eradicated in the United States by the year 2000. The United States does still see the occasional case of measles, however, most are traced back to travelers from foreign nations, where vaccinations are less mainstream. This has now changed, however.

How do Vaccines Work?

Vaccines help protect the body from viruses by stimulating the immune system to respond to a pathogen without causing the actual disease itself. Vaccines work by introducing a weakened or inactivated version of a pathogen, or in some cases, just a fragment of the pathogen called an antigen. This triggers white blood cells to produce antibodies, which are proteins that target and neutralize antigens.

The first time the immune system is exposed to pathogens, it takes some time for antibodies to be produced. Vaccines allow the immune system to recognize the pathogens of an illness, and memory cells in white blood cells are formed to “remember” the pathogen. This means that if a person is exposed to the pathogen in the future, their immune system will have an almost immediate response, protecting them against the disease.

Controversial Opinions – Fact or Fiction?

Despite vaccines’ long history of being safe and effective, more recent arguments claim that vaccines are a potential cause of autism. More specifically, the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR). After reports of children developing symptoms of autism after receiving the vaccine, politicians and organizations jumped on the idea.

The first dose of the MMR vaccine is administered to children 12-18 months old. Coincidentally, this is when the first signs of autism begin to show.

Since the Wakefield report, any direct connection between autism and the MMR vaccine has been discredited by dozens of studies investigating the epidemiology of autism and the biological effects of the MMR vaccine.

Following this, The World Mercury project was launched, supported by RFK Jr. The organization changed its name to Children’s Health Defense in 2018 and remains one of the most prominent forces on the anti-vaccine front.

A Drop in Vaccination Rates–What Does it Mean for the Future?

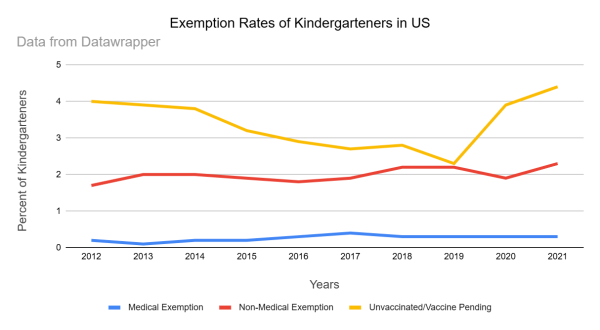

Along with the decreasing vaccination rates, the rate of exemptions are also increasing. Pairing these together could and has led to the United States population being more susceptible to possible outbreaks of diseases such as measles or polio.

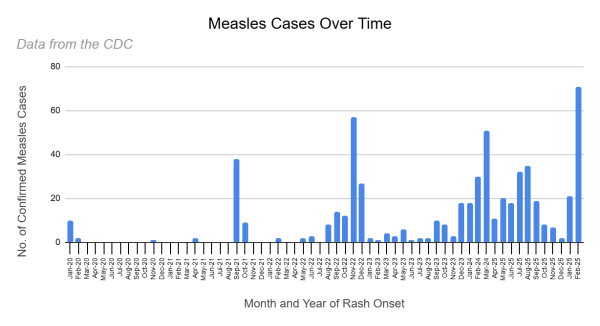

Increasing rates of measles, for example, could be directly correlated to the decreasing rate of childhood vaccinations. This graph shows how measles has had an exponential uptick in the United States.

Lessons from COVID

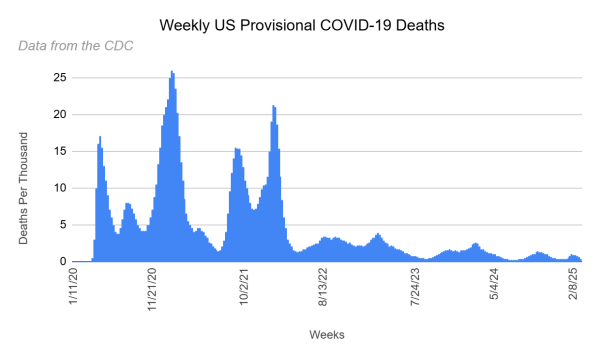

Recent outbreaks have raised parallels to the COVID-19 pandemic, which shuttered businesses and killed millions. In the early days of the pandemic, the only tools available for fighting COVID were masks and lockdowns. That is, until the COVID vaccine rolled out in late 2020, and was made widely available in the Spring of 2021. These graphs compare the rates of vaccinations per million to the death rate, per thousand.

As shown, the vaccine had a direct link to a drastic decrease in COVID deaths. Much like previous viruses such as polio or measles, a vaccine proved critical to allowing the world to re-open.

Outbreak or the Next Epidemic?

After much concern over recent vaccination rates, fears have come true in a rural part of Texas.

On February 13th, the Texas Department of State Health Services reported a measles outbreak in Gaines County. By the next day, the number of confirmed measles cases rose from 24 to 49.

The epicenter of this outbreak is the city of Seminole, a town in West Texas with a large Mennonite population, choosing to live there due to the loose rules on vaccinations in private schools.

Most of the initial cases occurred in school-age children, with 13 being hospitalized. All 13 were unvaccinated against measles, which is reflected in the county’s vaccination rates. As of the 2023-24 school year, Gaines County had an 13.6% exemption rate, one of the highest in the country.

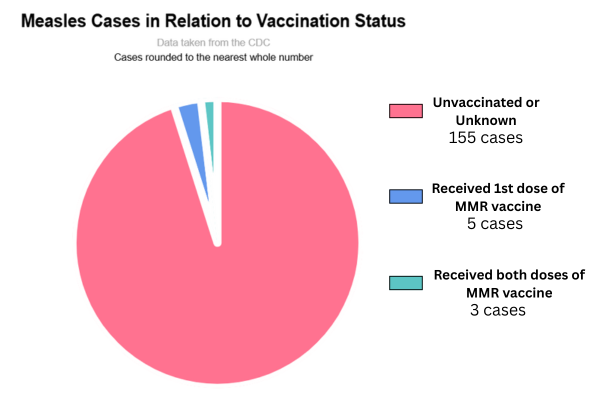

Low vaccination rates play a key role in this outbreak. 95% of measles cases were reported in unvaccinated individuals or those with unknown vaccination statuses. 3% occurred in individuals receiving one of the two doses of the vaccine, which provides some immunity, but not all, and only 2% of individuals with the virus were fully vaccinated. Receiving two doses of the vaccine provides 97% protection against the virus, with only three out of 100 fully-vaccinated individuals contracting measles.

As of February 28th, the first death, an unvaccinated school-age child, has occurred. 164 total cases have been recorded, and nine states have been affected. This is a testament to how quickly this virus can affect lives and wreak havoc.

In addition to an outbreak of measles in Texas, the bird flu (H5N1) has seen a spike among birds, especially poultry. American egg supplies have been historically empty after the bird flu has ravaged the American chicken population. Estimates now show that in the fourth quarter of 2024 (October, November, December), 45 million chickens died or were culled due to the bird flu. With this significant reduction in eggs, major retailers have instituted limits on the buying of eggs and raised prices on poultry products. Most concerningly, however, the bird flu has now mutated to be transmittable to the human population.

The CDC reports that, as of February 28th, in the United States, there have been approximately 70 cases of bird flu and one death, since concerns were raised in February 2024. It is reported that most of these infections were a result of exposure to either cattle or poultry, occurring most often in those who work in farming operations. While there is no known person-to-person spread at this time, this should be monitored as this virus mutates.

While an H5N1 vaccine has been available for poultry for decades, there is no vaccine available for humans as of yet, however, scientists are in the process of developing one, which would likely be effective in preventing spread in humans, as shown with previous virus outbreaks.

As of now, the rise of vaccine-preventable viruses is a concern in only a select few parts of the United States, however, this threat poses a silent risk to the rest of the nation due to sinking vaccination rates.

April Bowden • May 22, 2025 at 4:52 PM

I was surprised and frankly disappointed by how one-sided this article was in its portrayal of vaccines.

Why was there no mention of potential side effects or contraindications for people with pre-existing health conditions who cannot be vaccinated safely? A truly informed discussion must include the risks as well as the benefits. Even the manufacturers and the CDC acknowledge that no medical intervention is 100% risk-free.

Additionally, the article failed to address growing concerns about vaccine injury. The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), which has paid out over $4 billion to date, exists precisely because vaccine injury—though rare—does happen. This isn’t conspiracy theory; it’s federal policy. The fact that this was omitted from the article is a glaring oversight.

Furthermore, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), co-managed by the CDC and FDA, contains hundreds of thousands of reports annually. While not all are verified cases of injury, VAERS is meant to be an early warning system for potential safety issues. Shouldn’t this data be part of the conversation, especially when so many people report adverse effects?

I also find it concerning that the article did not mention conditions like transverse myelitis, which some researchers have linked to viral infections and, in rare cases, post-vaccination syndromes. It’s irresponsible to dismiss these discussions when people continue to report serious neurological complications following vaccines.

Finally, to claim that vaccines are universally “safe and effective” without qualification is an oversimplification. Science is rarely that absolute. Many people—myself included—have spent years researching this topic and have found troubling inconsistencies and unanswered questions in the official narrative. The CDC’s own data sometimes raises red flags that deserve open and transparent discussion.

Silencing or ignoring the opposition does not build public trust; it erodes it. A more nuanced, honest conversation is needed—one that respects both scientific inquiry and individual experience.