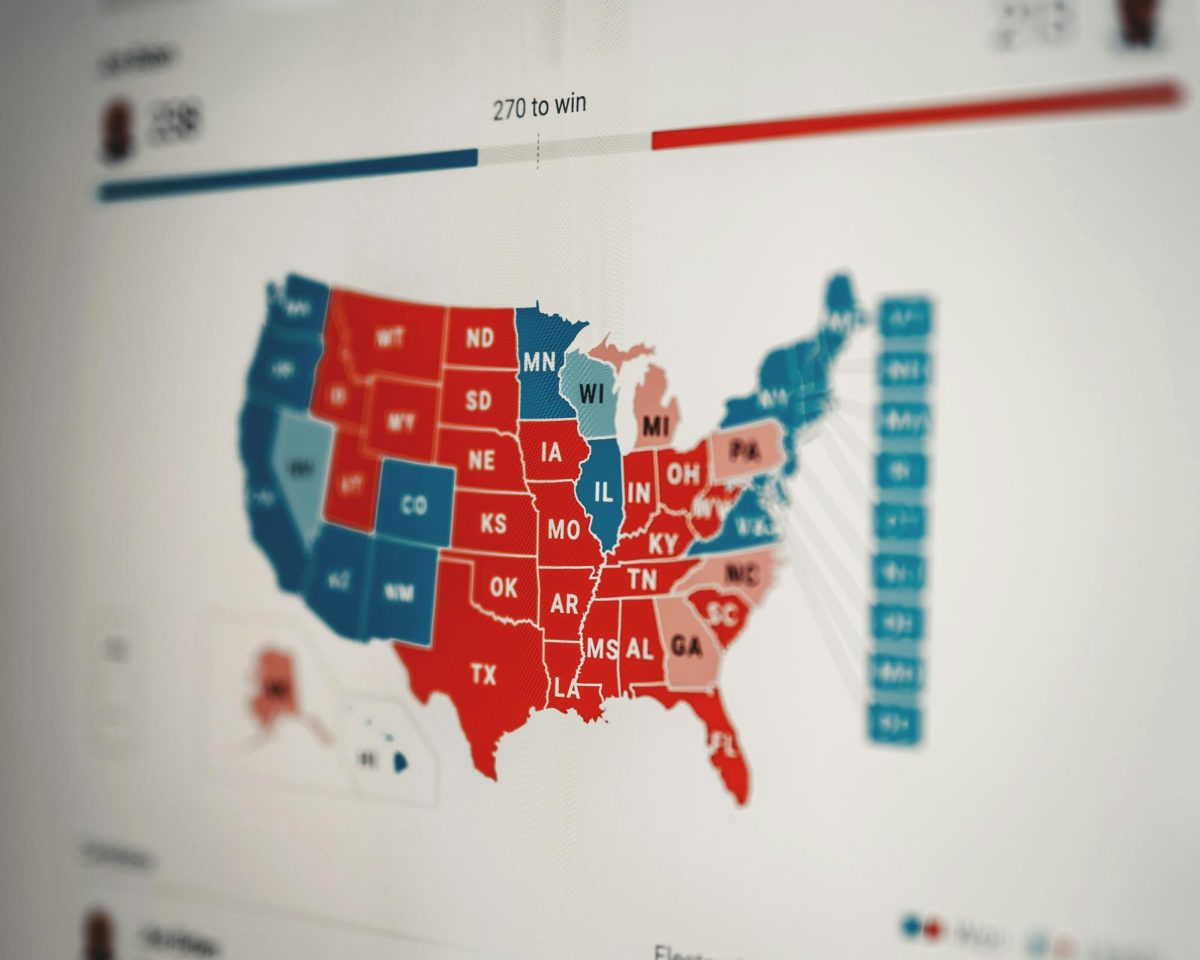

The Electoral College consists of 538 electors, with each state receiving a certain number of electors equivalent to its Senators and Representatives in Congress. An example is California, being the most populous state; it has 55 electoral votes, while a state like Wyoming has three. The District of Columbia also has three electoral votes while it is not a state. This ensures a proportion that takes into consideration not just population but also minimum representation for smaller states to ensure that all parts of the country have a voice in the presidential selection process.

In the presidential election, citizens vote not directly for a candidate but for a slate of electors promised to a certain candidate. Most states use a winner-takes-all system, whereby the candidate who receives the majority of the popular vote in that state takes all of that state’s electoral votes. Maine and Nebraska allocate their electoral votes proportionally to the votes each candidate received.

The electors, after counting all the votes, assemble in their respective state capitals in December and give their formal votes. These are then transmitted to Congress to be counted in a joint session in January. For a candidate to be elected president, they must have a majority of the electoral votes. This means that a presidential candidate must attain at least 270 of 538 electoral votes to win the presidency.

The whole idea of the Electoral College came from debates held during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The founding fathers wanted to create a system that would give voice equally to populous states and smaller ones. It was one means of assuring that informed, elite individuals—the electors—actually made the decision.

Over the years, numerous criticisms have been levied against the Electoral College. Critics say that undemocratically, it denies the principle of one person, one vote because a candidate may win the presidency without receiving the most popular votes nationwide, as occurred in the elections of 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016. Critics further contend that this system promotes candidates to focus campaign efforts and resources in swing states—those whose electoral votes are most in question—rather than addressing the needs of the entire electorate.

The advocates of the Electoral College argue that it helps to protect the rights of the smaller states by preventing regional candidates from dominating the elections. They further argue that it helps foster a national campaign strategy that is more extensive because candidates have to appeal to a variety of populations within different states.

The opponents, for their part, believe in reforming or abolishing the current system to replace it with a direct popular vote. To them, the current system disfranchises the voters in one-party-dominated states. They also term the instances of the Electoral College electing candidates that have not won the popular vote threats to democratic legitimacy.

The issues of the Electoral College have sparked intense debate in American politics for many years. Proposals ranged from state-by-state reforms to national constitutional amendments. Some states enacted the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, wherein a bloc of states would award their electoral votes to the candidate receiving the most popular votes nationwide, whether or not that candidate received the most votes within that particular state.

As the country goes forward, the issue of the efficiency and equity of the Electoral College will keep echoing. Whether this will change, reform, or remain intact is yet a matter of discussion that shall shape the future of American democracy. The Electoral College was representative—and still is—of the complex history and implications in which America elects her leaders.